Cognitive Science30(2006)381–399

Copyright ?2006Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved.

Culture and Change Blindness

Takahiko Masuda a, Richard E. Nisbett b

a Department of Psychology, University of Alberta

b Department of Psychology, University of Michigan

Received 11 November 2004; received in revised form 17 October 2005; accepted 8 November 2005

Abstract

Research on perception and cognition suggests that whereas East Asians view the world holistically, attending to the entire field and relations among objects,Westerners view the world analytically,focus-ing on the attributes of salient objects.These propositions were examined in the change-blindness para-digm.Research in that paradigm finds American participants to be more sensitive to changes in focal ob-jects than to changes in the periphery or context.We anticipated that this would be less true for East Asians and that they would be more sensitive to context changes than would Americans.We presented participants with still photos and with animated vignettes having changes in focal object information and contextual https://www.doczj.com/doc/d62103495.html,pared to Americans,East Asians were more sensitive to contextual changes than to focal object changes.These results suggest that there can be cultural variation in what may seem to be basic perceptual processes.

Keywords:Culture; Attention; Change blindness; Change detection; Holistic vs. Analytic thought; Japanese; Americans; Cultural psychology

1.Introduction

Westerners and East Asians differ in their judgments about causality for events,both physi-cal and social.Westerners tend to locate causality in the object,whereas East Asians are more likely to call on the field or context as well(e.g.,Morris&Peng,1994;Norenzayan&Nisbett, 2000; Peng & Knowles, 2003).

Nisbett and his colleagues(Ji,Peng,&Nisbett,2000;Nisbett,2003;Nisbett,Peng,Choi,& Norenzayan,2001)have argued that these different tendencies in causal attribution,as well as other perceptual and cognitive differences between Asians and Westerners,are due in part to differences in attention to the object versus the context.East Asians live in highly interdepen-dent societies.They must attend to their relationships with other people before they can take action with respect to personal goals.Westerners,in contrast,live in more independent societ-Correspondence should be addressed to Takahiko Masuda,Department of Psychology,University of Alberta, P-355, Biological Sciences Building, Edmonton, AB, Canada, T6G 2E9. E-mail: tmasuda@ualberta.ca

382T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)

ies allowing relatively socially unimpeded attention to personal goals with respect to important objects.Because attention is directed toward the social world for East Asians,causality is seen to inhere substantially in the context.As Markus and Kitayama(1991,p.246)put it,“If one perceives oneself as embedded within a larger context of which one is an interdependent part,it is likely that other objects or events will be perceived in a similar way.”Because attention is fo-cused on salient objects for Westerners,in contrast,it is natural for them to attribute causality to objects.

Masuda and Nisbett(2001)obtained evidence for the predicted attentional differences by showing American and Japanese college students animated vignettes of underwater scenes and subsequently asking the participants what they had seen.They found that the American partici-pants tended to begin by referring to the most salient objects in the vignettes(that is,the larg-est,brightest,most rapidly moving objects).They were likely to say,“I saw what looked like a trout swimming off to the left.”Japanese participants were much more likely to begin with the context.They were likely to say,“I saw what looked like a stream;the water was green;there were rocks on the bottom.”The Japanese participants reported more than60%more details about the context than did the American participants.

The Japanese participants also appeared to see the objects in relation to the context.After participants had been shown eight vignettes,they were shown individual objects.Half of these had been seen before and half had not.Some were shown with their original backgrounds and some were shown in novel backgrounds.Japanese participants showed a“binding”effect (Chalfonte&Johnson,1996);that is,the accuracy of their reports as to whether or not they had seen an object was thrown off if they saw the object in an environment different from the one in which it had initially appeared.American participants were not affected by the background manipulation.

It would be valuable to have additional evidence on the question of whether the attention of Westerners and East Asians is directed differently.One paradigm that seems a promising one for investigation is the so-called change-blindness paradigm.Previous research has shown that people often fail to recognize marked changes in their surroundings(Simons,2000;Simons& Levin,1998).For example,when people are asked to watch a videotape and count the number of ball passes between players,they consistently fail to notice the insertion of an unusual char-acter into the scene,such as a person carrying an umbrella or even a person wearing a gorilla costume(Simons&Chabris,1999).Change blindness is evident even when participants are explicitly asked to search for changes in the visual field.For example,various researchers have used the“flicker”paradigm in which an original image repeatedly alternates with a second im-age until the participant recognizes the change(Rensink,O’Regan,&Clark,1997).Partici-pants often take a great deal of time to detect major changes in a given scene.A generalization emerging from this research is that people are likely to detect changes in salient,focal objects faster than in objects in the periphery or context(Rensink et al.,1997;Scholl,2000).In this re-search,we compared the change blindness of Americans and Japanese.We expected to find the Japanese to be more focused on changes in the context than Americans.

If the anticipated differences were to be found,we believe that the explanation would be found in cultural differences between East Asians and Westerners.First,East Asians are so-cialized to attend to contexts,including both physical and socioemotional contexts.Bornstein, Toda,Azuma,Tamis-LeMonda,and Ogino(1990)and Fernald and Morikawa(1993)studied

T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)383 Japanese and American mothers and their infants and found that the American mothers di-rected their infants’attention primarily to objects,whereas Japanese mothers directed their in-fants’attention alternately to objects and to the mother’s face,thereby encouraging attention to social factors at the same time the object was being examined.The Japanese mothers also em-phasized interactive social routines(“I give it to you.You give it to me.Yes!Thank you”). Tardif,Shatz,and Naigles(1997)found that American mothers use more nouns(i.e.,words re-ferring to objects)when speaking with their infants.In contrast,Chinese mothers use relatively more verbs(i.e.,words primarily referring to relationships in the environment or between the infant or mother and the environment).Second,as we will show later,there is evidence that Asian-built environments are more complex than Western environments.The complexity of the environment could serve to draw habitual attention to the context as opposed to salient ob-jects(Chun,2000).Either or both cultural factors could prompt differential attention of Asians and Westerners.

2.Experiment 1

2.1.Method

2.1.1.Materials

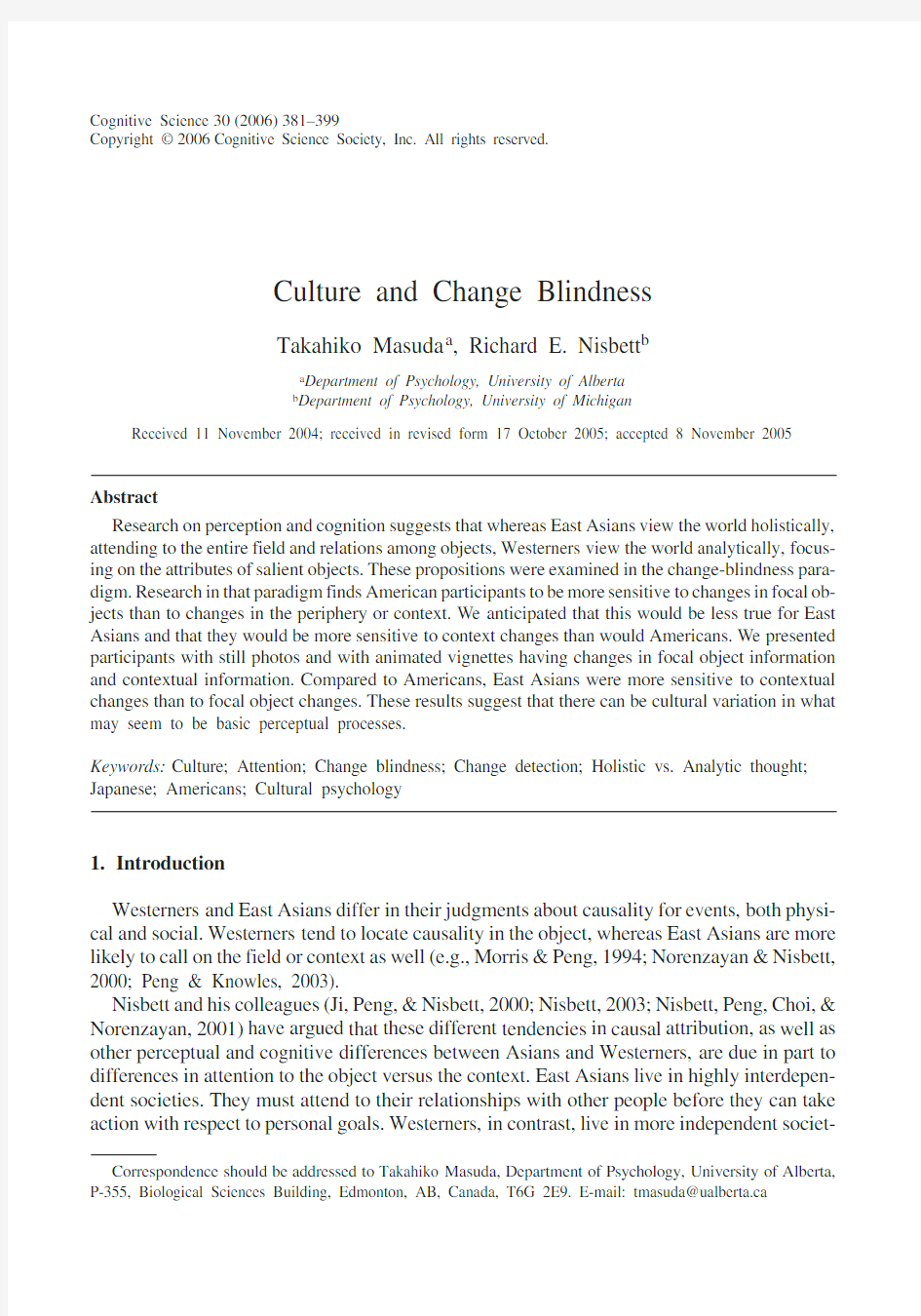

Following the original flicker paradigm(Rensink et al.,1997),we created a set of flicker se-quences of images,in which an original image and a modified image were presented in the se-quence A,A′,A,A′…,with a blank field presented between two images(Fig.1).Each image was presented for560msec,and the blank field was presented https://www.doczj.com/doc/d62103495.html,ing PsyScope, 30pairs of slightly different color images of realistic industrial scenes were prepared—an air-port,a construction site,a town,a farm,and a harbor.Each image contained focal objects(e.g., foregrounded machines) as well as contexts (e.g., background buildings).

In each pair of images,there occurred only one change,which was either a change in focal object information(e.g.,focal vehicle’s color)or a change in contextual information(e.g., changes in the location of clouds).We believe that the objects that underwent changes were all typical of the scenes they had appeared in(see Appendix A).The alternation continued for a minute,and images disappeared if participants could not detect the changes within a minute. 2.1.2.Participants and procedure

Thirty American students(15women and15men)and36East Asian international students (Chinese,Japanese,or Korean;17women and19men)at the University of Michigan partici-pated in the experiment as a course requirement or for$10.1About two thirds of participants in both populations were paid.After greeting the participants,the experimenter escorted each to a https://www.doczj.com/doc/d62103495.html,ptop computer(Macintosh Powerbook G3)presented the images,which were22-cm wide and16.5-cm high.Viewing distance(30cm)and angle(about40.7°×31.5°) from the monitor were standardized by asking participants to sit in chairs with their chins rest-ing on a small platform.The experimenter explained that the participants’task was to view quick alternations of a pair of images and to identify the differences between the first and sec-ond images.As may be seen in Appendix A,participants were presented30different pairs of

scenes.The instructions were identical for both cultural groups.(For this and the other two studies,we used the back translation technique to assure equivalence.)Participants were asked to press a key when they recognized the change and later to report it orally.Experimenters checked whether their identification of changes were correct or not.Only 4.5%of the re-sponses were coded as a “miss”or “run out of time.”2We analyzed only the data for which par-ticipants correctly detected the changes within 60 sec.

2.2.Results

2.2.1.Manipulation check

After the experiment,we asked the same participants to identify what they regarded as the central objects of the 30scenes.The results of chi-square analyses indicated that,for all 30im-ages,there were no significant cultural differences in the objects that the participants identified as central.Overall,84%of Americans and 83%of East Asians indicated that they identified as central objects those that corresponded to the experimenter’s intention.3

2.2.2.Change detection

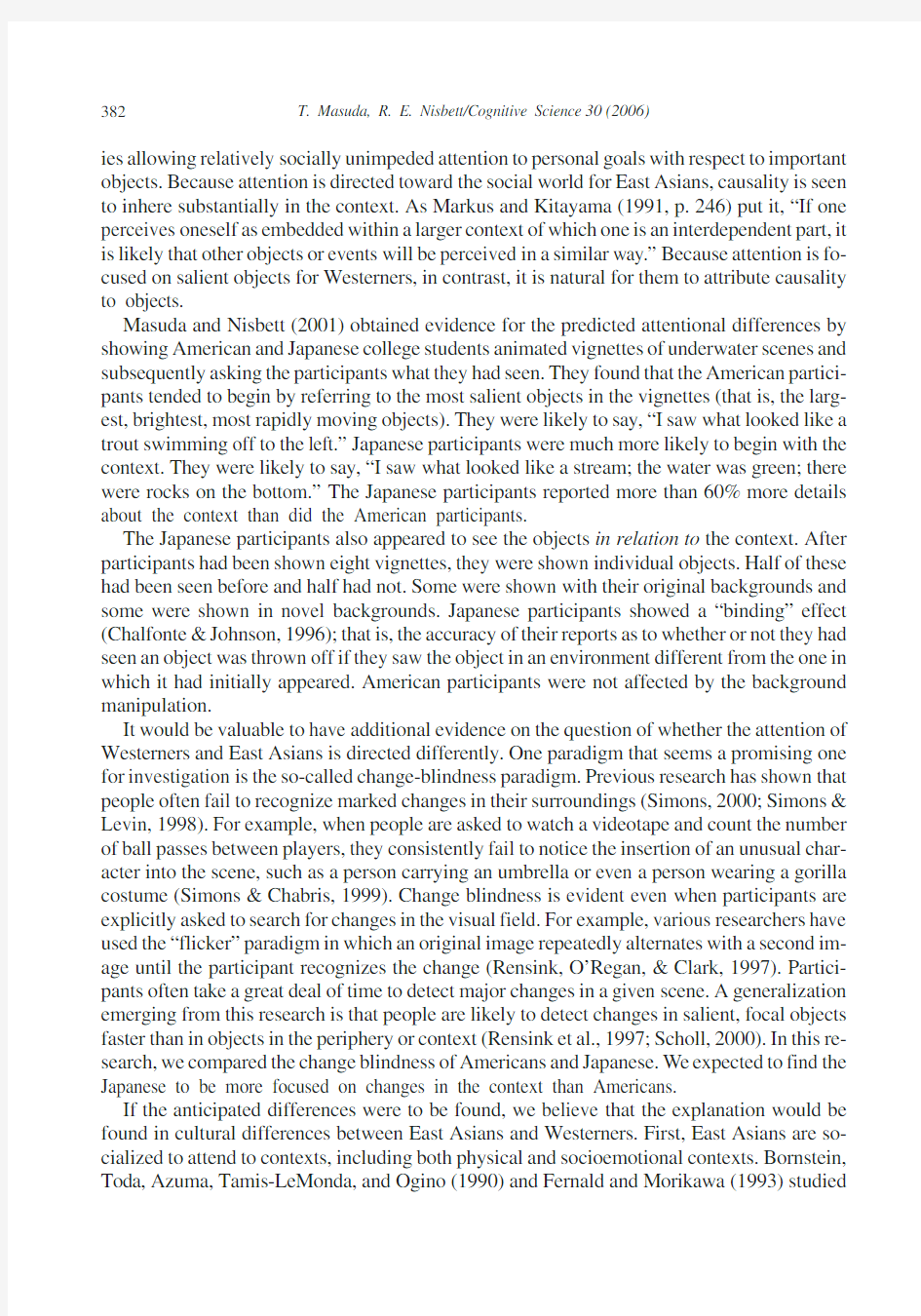

A 2(culture:Americans vs.East Asians)×2(type of change:object vs.context)analysis of variance(ANOV A)ofreactiontimefortheidentificationofchangesshowninFig.2revealedthat

384T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30

(2006)

Fig.1.Examples of changes in industrial scenes.The wheel of the bicycle in Picture A disappears in Picture A ′.The location of sidewalk at the left bottom area in Picture B has been changed in Picture B ′.

there was an interaction of culture and type of change,F (1,64)=3.96,p =.05.4A planned con-trast analysis indicated that East Asians detected changes in contextual information faster than did Americans,F (1,64)=4.02,p <.05.Another contrast showed that American participants de-tected changes in the focal objects faster than changes in contextual information,F (1,64)=5.45,p <.03.East Asian participants detected context changes as rapidly as object changes.

These results indicate that East Asian participants attended to the contextual information more than did Americans.As in previous research,American detection of object changes was more rapid than detection of context changes,but this was not true for East Asian participants.Thus the generalization in the change-blindness literature that focal object changes are more detectable than context changes held only for the American participants in this study.

3.Experiment 2

The data from the flicker paradigm provides us with evidence of cultural variation in ways of seeing visual scenes.However,the task dealt only with still images.Several researchers have investigated change blindness for continuous movement or dynamic stimuli in the real world (e.g.,Levin &Simons,1997;Simons &Chabris,1999;Simons &Levin,1998).Using their basic methodology,we showed a movie clip for 20sec.Instead of using the most common measure of change detection in previous studies,namely,reaction time,we examined the num-ber of detected changes in two types of information—focal object information and contextual information.Because perception of naturalistic scenes was our primary interest,we developed animated vignettes in which realistic objects were shown against meaningful backgrounds.In these vignettes changes occurred simultaneously in various respects,including the attributes of focal objects as well as backgrounds and the location and movement of objects.We anticipated that cultural differences in the detection of change would be particularly likely to emerge under T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30(2006)

385

Fig. 2.Reaction time for change identification in Experiment 1.

conditions of heavy attentional load,in which multiple changes occur in both the focal objects and the context of the scene (cf. Kelley, Chun, & Chua, 2003; Ro, Russell, & Lavie, 2001).

3.1.Method

3.1.1.Materials

We created five pairs of animated color vignettes,using Macromedia’s Director7 (Macromedia,San Francisco,California),which were slightly different from each other. Black-and-white stills from the airport vignettes are shown in Fig.3.As may be seen in Appen-dix B,all animated vignettes included three to four focal objects(e.g.,aircraft),some of which moved and the rest of which were stable and situated either in the foreground or in the mid-dle-range area.In addition,all scenes included several background objects,such as ground, sky,and buildings.Again,the objects that underwent changes were all typical of the scenes they had appeared in.The length of each animation was20sec.Participants were asked to de-tect changes between the first and second animated sequence of the same scene.

386T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30

(2006)

Fig.3.An example of a vignette(a set of movie clips)used in Experiment2,consisting of four distinct pictures. Picture A represents the first part of Airport clip1.Picture B represents the last part of Airport clip1.This sequence was presented for20sec.After the2sec break,Airport clip2was presented.Picture C represents the first part of Airport clip2,and Picture D represents the last part of Airport clip2.Between Clip1and Clip2,various changes in a foreground object’s attributes,in a foreground object’s location,in background,and in a foreground object’s movement occur.

Fig.4illustrates the two types of change manipulated:change in focal object information (e.g.,machines)and change in contextual information (e.g.,background objects and object location).

The same 17-in.(about 43cm)Macintosh color monitor (about 33cm wide ×25cm high)and computer (Macintosh G3)were used in both the American and Japanese laboratories.Viewing distance (40cm)and angle (about 44.8′×34.7)from the monitor was standardized by asking participants to sit in chairs with their chins resting on a small platform.

3.1.2.Participants and procedure

The groups were matched as closely as possible across the two countries.Nineteen under-graduate American students at the University of Michigan (9women and 10men,age range:T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30(2006)

387

Fig.4.Examples of changes in focal object information and in contextual information.All pictorial information is presented in Fig.3.In section A “changes in focal objects information,”the airline logo and the landing gear de-picted in the left picture have been removed in the right picture.In section B “changes in contextual information,”there are three subcategories.In (a)“changes in background,”the helicopter in the left picture was replaced toward the right of its position in the right picture.In (b)“changes in objects’location,”the control tower situated in the background appears as a round building (left),having appeared as a rectangular building (right).The last line indi-cates the definition of (c) “changes in objects’movement.”

388T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)

18–22,M=19.4)and18undergraduate Japanese students at Kyoto University in Japan(8 women and10men,age range:18–21,M=19.3)participated in the experiment as a course re-quirement.After greeting participants,the experimenter escorted each one to a cubicle.The experimenter explained that the participant’s task was to view five vignette pairs and to deter-mine the differences between the first and second vignettes.Participants were allowed to watch each pair of vignettes four times.After each viewing of a pair of sequences,participants were asked to describe the changes they saw on a sheet of paper in as specific and concrete terms as possible.The participants were also allowed to correct their answers if they thought they had made a mistake.Half of the participants from each culture watched the animations in the order listed previously and half in the reverse order.

3.1.3.Data coding

Three Japanese–English bilingual coders(two Japanese-born,one American-born)coded each sentence as referring to one of the two categories of change.One coded the entire data set, whereas the two others coded half of the data.Agreement was94%.To ensure that language did not influence their coding,a bilingual translator translated one third of the Japanese data into English and one third of the American data into Japanese.A monolingual American and a monolingual Japanese then coded these data.Their agreement was93%.We used the first set of coded data for the analyses(with disagreements among coders decided by the first author). Coders agreed that5.4%of the responses were incorrect answers.5We examined only the cor-rect responses in further analyses.

3.2.Results

For each participant,we computed the mean number of detections of focal object changes and the mean number of detections of context changes across all five scenes and summarized across individual means to determine the group tendency in attention allocation.The mean number of changes detected in focal object information and contextual information is shown in Fig.5.A2(culture)×2(object vs.context)ANOV A showed that there was an interaction be-tween culture and allocation of attention,F(1,35)=9.44,p<.005.Simple effect analyses re-vealed that Japanese participants were more likely than American participants to detect changes in contextual information,F(1,35)=5.68,p<.03.American participants were mar-ginally more likely than Japanese participants to detect changes in focal object information, F(1, 35) = 2.92, .05 4.Experiment 3 In Experiment3,we attempted to replicate and extend Experiment2.Except for the airport and construction scenes,the stimuli used in Experiment2consisted of distinctly American scenes.6In Experiment3,we added additional scenes consisting of realistic pictorial materials that appeared to be Japanese.The two types of material differed in many ways,but the most relevant for present purposes was that the American scenes were object oriented.This means that there were relatively few objects,the objects were highly distinct and salient,and the back-grounds were relatively simple.The Japanese scenes,in contrast,were highly complex,con-taining many objects that were relatively difficult to distinguish from their backgrounds.These differences capture what the work of Miyamoto,Nisbett,and Masuda (in press)has shown to be ecologically typical of the respective countries.These investigators photographed 1,000scenes close to randomly chosen schools,hotels,and post offices in large cities,medium-size cities,and villages in the United States and Japan.In all town sizes they found the Japanese en-vironments to consist of more objects and to be more complex,as measured both subjectively and objectively. 4.1.Method 4.1.1.Materials and preliminary experiment In addition to previous vignettes created using basically American pictorial sources,we added two Japanese scenes:a Japanese town and a Japanese farm (see Appendix B).To de-termine the cultural specificity of each vignette,we asked 31American participants and 31Japanese participants to evaluate whether these pictures represented Japanese scenery,American scenery,or scenery that could be seen in both cultures.To make their evaluations,participants used a 7-point scale (1=strongly represents Japanese scene,7=strongly repre-sents American scene ).As we anticipated,the airport scene and the construction scenes were evaluated as common to both cultures (average M =4.32).The scenes of a town,a farm,and a harbor from Experiment 2were regarded as more likely to represent American scenery (average M =5.13).Finally,the new Japanese town scene and the new Japanese farm scene were regarded as more likely to represent Japanese scenery (average M =1.73;see Fig.6). T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30(2006) 389 Fig. 5.Average number of detected changes for all vignettes in Experiment 2. 4.1.2.Participants and procedure Again,the groups were matched as closely as possible across the two countries.Twenty-eight undergraduate American students at the University of Michigan (15women and 13men,age range:18–21,M =18.8)and 32undergraduate Japanese students at Kyoto Univer-sity in Japan (17women and 15men,age range:18–25,M =19.9)participated in the experi-ment as a course requirement.As in Experiment 2,participants saw five vignettes.All the par-ticipants saw the two culturally neutral scenes—the airport and the construction site vignettes.In addition,participants saw three of the culturally specific scenes—either two American and one Japanese or two Japanese and one American. 4.1.3.Data coding The same coding procedures used for Experiment 2were applied.Agreement among three coders was 93%.Agreement of a monolingual American and a monolingual Japanese was 92%.Coders agreed that 5.3%of the responses were incorrect answers.We analyzed only the correct responses. 390T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30 (2006) Fig.6.Example images used in Experiment 2.Images A (farm)and B (town)represent Japanese scenes.Images C (farm) and D (town) represent American scenes. Original stimuli are animated vignettes. 4.2.Results The number of detected changes in both categories is shown in Fig.7.A 2(culture)×2(object vs.context)ANOV A for the average reports for the five scenes showed that there was a significant interaction between culture and allocation of attention,F (1,58)=22.72,p <.001.Simple analyses revealed that Japanese participants were more likely to detect changes in contextual information than were Americans F (1,58)=16.17,p <.001.Ameri-cans were more likely to detect changes in focal object information than the Japanese,F (1, 58)=5.63,p <.02.The patterns for culturally neutral scenes and culturally specific scenes were similar,with the exception that the difference in change detection for focal objects for culturally neutral scenes was slight and insignificant.Overall,we replicated the findings of Experiment 2but with much stronger results—undoubtedly primarily due to the increased number of participants. We also found a significant interaction between allocation of attention and type of cultural scene,F (1,58)=128.62,p <.001.7Fig.8shows the responses of both Americans and Japanese to U.S.scenes and the responses of both groups to Japanese scenes.Simple effect analyses re-vealed that both Japanese and American participants detected changes in focal object informa-tion in American scenes more often than in Japanese scenes,F (1,58)=11.96,p <.001.More-over,both Japanese and American participants detected changes in contextual information in Japanese scenes more often than in American scenes,F (1,58)=7.74,p <.001.There was no significant interaction between culture and type of scene.Thus,American scenes appear to have facilitated attention to foreground objects,whereas Japanese scenes facilitated attention to relationships and background.These results suggest that environments characteristic of dif-ferent cultures direct people’s attention differently. T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30(2006) 391 Fig. 7.Average number of detected changes for all vignettes in Experiment 3. 5.General discussion This research provides evidence that cultural variations are observable even in patterns of attention that one might assume to be governed by basic,invariant psychological processes.In Experiment 1we found that Japanese participants detected changes in context information more rapidly than did American participants,whereas there was no difference in how rapidly the two groups detected changes in object information.As has been found by the research of others,Americans detected object changes more rapidly than changes in context information,but the two types of information were detected equally rapidly by Japanese participants.In Ex-periments 2and 3we found that Americans detected more object changes than Japanese but that Japanese detected far more context changes than object changes. 6.Reasoning style, visual experience, and attention Why might Easterners and Westerners allocate their attention differently?Past theorizing by Nisbett and his colleagues (Nisbett,2003;Nisbett,Peng,Choi,&Norenzayan,2001)has emphasized socialization differences that begin very early.Although it is likely that such so-cialization differences are indeed important,these results suggest that the affordances of the environments that Asians and Westerners confront also play a role.Miyamoto et al.(in press)sampled 1,000scenes from American and Japanese towns and found Japanese towns to con-tain more objects and be more complex.Eastern environments thus may focus attention on context.That this hypothesis is plausible is indicated by the results of a study by Miyamoto et al.They primed participants either with photographs they had taken of American scenes or with photographs of their Japanese scenes.They then examined American and Japanese re- 392T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science 30 (2006) Fig. 8.Average number of detected changes for culturally specific vignettes in Experiment 3. T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)393 sponses to a change-blindness task using the culturally neutral pictures from Experiment3of this research.Participants—both American and Japanese—primed with Japanese scenes saw more changes in contexts than did participants primed with American scenes.This result is consistent with findings indicating that learned visual experience pertaining to contextual fac-tors shapes the way individuals allocate attention (Chun, 2000). Although there is evidence that environmental affordances make a contribution to the cul-tural differences in attention that we have found,we do not believe this is the whole story. There are many studies showing greater attention to context by Asians,not only in other atten-tion domains(Ishii,Reyes,&Kitayama,2003),but also in memory(Hedden et al.,2000;Liu &Nisbett,2005;Masuda&Nisbett,2001)and even inference processes,including causal rea-soning(Choi,Nisbett,&Norenzayan,1999;Masuda&Kitayama,2004;Miyamoto& Kitayama,2002;Morris&Peng,1994;Norenzayan&Nisbett,2000).Thus,although it is likely that ecological factors play a role in attentional differences,the fact that parents socialize different patterns of attention and the fact that cultural differences are found for a wide variety of attention and reasoning tasks indicate that environmental affordances should not be re-garded as the sole cause of the effects we have reported. 7.Cultural difference in attention Are the cultural variations found in these studies attributable to genuine differences in attentional processes?We believe there is good evidence for that.The responses in Experi-ments2and3were verbal descriptions for which it may not be possible to completely elimi-nate differences in language or conversational rules.But responses in Experiment1were reac-tion times.Moreover,the findings of eye-tracking studies give credence to the assertion that there are genuine attentional differences.For example,Masuda et al.(2005)presented partici-pants with a series of cartoon images,consisting of a target figure in the center and four back-ground figures in the peripheral area,and asked participants to judge the central figure’s emo-tion based on his facial expression.The results indicated that East Asians were more likely than their North American counterparts to allocate their attention to the peripheral figures’fa-cial expressions and that their judgment were strongly influenced by the changes in the back-ground figures’facial expression.Similarly,Chua,Boland,and Nisbett(2005)presented par-ticipants with a set of stimuli consisting of a central object and background scene.Results indicated that Americans looked at central objects sooner and longer and that Asian partici-pants made more eye movements to the background(as well as more total eye movements).In sum,these findings suggest that East Asians’tendency to physically allocate their attention to contextual information is much stronger than that of North Americans. Identification of the stage where culture can affect vision is beyond the scope of this re-search.Here,we are content with maintaining that systematic cultural influences,via social-ization and probably also environmental affordances,do occur somewhere in the process of vi-sion,and this influence cannot be considered a negligible factor in better understanding the relations between perception and cognition.These findings support the notion that it is differ-ences in attention that underlie other differences in reasoning styles characterized by Nisbett 394T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006) and his colleagues as holistic(more typical of East Asians)versus analytic(more typical of Westerners).If attention is distributed quite differently between object and context for East-erners and Westerners,that fact would seem sufficient on the face of it to explain differences in causal attribution:What you see is what you attribute to—and Westerners are relatively more likely to see objects, whereas Easterners are relatively more likely to see contexts. Notes 1.East Asian participants refer to those who lived in their countries at least till their high-school or undergraduate-level graduation(undergraduate participants)and who were categorized as international students by university criteria.All the East Asian par-ticipants had lived in the United States less than5years.American participants were2 graduate students(1woman and1man,age range:29–31,M=30.00)and28under-graduate students(14females and14males,age range:18–21,M=19.07).East Asian participants were20graduate students(7women and13men,age range:22–34,M= 28.85)and16undergraduate students(10women and6men,age range:18–23,M= 20.25).A2(the school status)×2(the type of changes)ANOV A was applied to their per- formance within culture,which indicated that there was no significant interaction be-tween the type of changes and the school status as to their performance,F<1,ns;F(1, 34) = 1.07,ns,respectively. So, we collapsed across the factor of the school status. 2.A2(culture:East Asians vs.Americans)×2(run out of time:objects vs.contexts) ANOV A indicated that there were no main effects of culture,F<1,nor run out of time, F(1, 64) = 2.87,ns.The interaction was not significant,F< 1. 3.The experimenter first set in advance the central objects in each scene.Next,if partici- pants selected the intended objects,we assigned the value“1.”If participants selected unintended objects in the context,we assigned the value“2.”Overall,83.50%of the participants’data(84%of Americans’and83%of East Asians’)were categorized as Value1.Then we created a series of contingency tables of culture(Americans vs.Japa-nese)and selected objects(Value1or2)and carried out chi-square analyses on each scene.The logic was that if there was a significant difference between American and Japanese interpretation of centrality,then the chi-square values should be statistically significant.But,if there are no statistically significant differences in the values,we can conclude that our manipulation was effective,and there are no statistically significant cultural differences in centrality.In a total of30chi-square analyses for30scenes,no chi-square values were statistically significant,which suggests that there was good agreement between American and East Asian participants. 4.All p values are based on two-tailed tests. 5.To minimize the influence of differences in language,we instructed participants to write their answer as concretely as possible(e.g.,“a red car’s wheel has been changed).Bilin-gual coders were trained to become familiar with the types of changes in the scene. Based on their judgment,we accepted relatively vague expressions such as(a part of the front car has been changed)but judged as wrong ambiguous expressions such as“some-thing has been changed.” T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)395 6.The pattern of results found in Fig.5was found both in the scenes that we regarded as culturally neutral—the airport and construction scenes—and in the culturally specific scenes.Of the possible comparisons between Japanese and Americans,only the differ-ence in report of context differences for the neutral scenes was statistically significant by itself. 7. A three-way interaction was not statistically significant,F(3, 58) = 2.25,p> .10. Acknowledgments This study was supported by National Science Foundation Grants SBR9729103and BCS0132074.,We thank Janxin Leu,Julia S.Carlson,Paul Graham,Nicholas W.Kohn,Keiko Ishii,Carrie Hoi-Suen Lee,Chinae Masuda,Yuri Miyamoto,Mark H.B.Radford,James M. Shields, Margaret Wen-Ching Su, and Mitsuko Yakabi for their assistance. References Bornstein,M.H.,Toda,S.,Azuma,H.,Tamis-LeMonda,C.,&Ogino,M.(1990).Mother and infant activity and in-teraction in Japan and in the United States II:A comparative microanalysis of naturalistic exchanges focused on the organization of infant attention.International Journal of Behavioral Development, 13,289–308. Chalfonte,B.L.,&Johnson,M.K.(1996).Feature memory and binding in young and older adults.Memory and Cognition, 24,403–416. Choi,I,Nisbett,R.E.,&Norenzayan,A.(1999).Causal attribution across cultures:Variation and universality.Psy-chological Bulletin, 125,47–63. Chua,H.F.,Boland,J.,&Nisbett,R.E.(2005,January).Attention to object vs.background:Eyetracking evidence comparing Chinese and Americans.Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, New Orleans, LA. Chun, M. M. (2000). Contextual cueing of visual attention.Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4,170–178. Fernald,A.,&Morikawa,H.(1993).Common themes and cultural variations in Japanese and American mothers’speech to infants.Child Development, 64,637–656. Hedden,T.,Ji,L.,Jing,Q.,Jiao,S.,Yao,C.,Nisbett,R.E.,et al.(2000,April).Culture and age differences in recog-nition memory for social dimensions.Paper presented at the Cognitive Aging Conference, Atlanta, GA. Ishii,K.,Reyes,J.A.,&Kitayama,S.(2003).Spontaneous attention to word content versus emotional tone:Differ-ences among three cultures.Psychological Science, 14,39–45. Ji,L.J.,Peng,K.,&Nisbett,R.E.(2000).Culture,control,and perception of relationships in the environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78,943–955. Kelley,T.A.,Chun,M.M.,&Chua,K.-P.(2003).Effects of scene inversion on change detection of targets matched for visual salience.Journal of Vision, 2,1–5. Levin,D.T.,&Simons,D.J.(1997).Failure to detect changes to attended objects in motion pictures.Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 4,501–506. Liu, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (2005). [Contextual effects on the test performance]. Unpublished raw data. Markus,H.,&Kitayama,S.(1991).Culture and the self:Implications for cognition,emotion,and motivation.Psy-chological Review, 98,224–253. Masuda, T., Ellsworth, P. C., Mesquita, B., Leu, J.-X., Tanida, S., & van de Veerdonk, E. (2005). Placing the face in context:Cultural differences in the perception of facial behavior of emotion.Manuscript submit-ted for publication. 396T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006) Masuda,T.,&Kitayama,S.(2004).Perceiver-induced constraint and attitude attribution in Japan and the US:A case for the cultural dependence of the correspondence bias.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,40, 409–416. Masuda,T.,&Nisbett,R.E.(2001).Attending holistically versus analytically:Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81,922–934. Miyamoto,Y.,&Kitayama,S.(2002).Cultural variation in correspondence bias:The critical role of attitude diagnosticity of socially constrained behavior.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,83,1239–1248. Miyamoto,Y.,Nisbett,R.E.,&Masuda,T.(in press).Differential affordances of Eastern and Western environ-ments.Psychological Science. Morris,M.W.,&Peng,K.(1994).Culture and cause:American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67,949–971. Nisbett,R.E.(2003).The geography of thought:How Asians and Westerners think differently…and why.New York: Free Press. Nisbett,R.E.,&Masuda,T.(2003).Culture and point of view.Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 100,11163–11175. Nisbett,R.E.,Peng,K.,Choi,I.,&Norenzayan,A.(2001).Culture and systems of thought:Holistic vs.analytic cognition.Psychological Review, 108,291–310. Norenzayan,A.,&Nisbett,R.E.(2000).Culture and causal cognition.Current Direction in Psychological Science, 9,132–135. Peng,K.,&Knowles,E.(2003).Culture,ethnicity and the attribution of physical causality.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29,1272–1284. Rensink,R.A.,O’Regan,J.K.,&Clark,J.J.(1997).To see or not to see:The need for attention to perceive changes in scenes.Psychological Science, 8,368–373. Ro,T.,Russell,C.,&Lavie,N.(2001).Changing faces:A detection advantage in the flicker paradigm.Psychological Science,12,94–99. Scholl,B.J.(2000).Attenuated change blindness for exogenously attended items in a flicker paradigm.Visual Cognition,7,377–396. Simons, D. J. (2000). Current approaches to change blindness.Visual Cognition, 7,1–15. Simons,D.J.,&Chabris,C.F.(1999).Gorillas in our midst:Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28,1059–1074. Simons,D.J.,&Levin,D.T.(1998).Failure to detect changes to people during a real-world interaction. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 5,644–649. Tardif,T.,Shatz,M.,&Naigles,L.(1997).Caregiver speech and children’s use of nouns versus verbs:A compari-son of English, Italian, and Mandarin.Journal of Child Language, 24,535–565. T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)397 Appendix A. Types of Scenes and Changes of the Stimulus Set Used in Experiment 1 No.Scenes Changes Change Category Type 1.Airport Front plane’s color Focal object Property change 2.Airport Number of window of the plane Focal object Deletion/Addition 3.Airport Size of the front plane’s engine Focal object Form change 4.Airport Background control tower’s shape Context Form change 5.Airport Cloud’s shape Context Form Change 6.Airport Helicopter’s location Context Location 7.Construction site Front bulldozer’s lights (on/off)Focal object Property change 8.Construction site Front bulldozer’s shape of gear Focal object Deletion/Addition 9.Construction site Front bulldozer’’s line color Focal object Form change 10.Construction site Number of construction frames Context Deletion/Addition 11.Construction site Electric lines in background Context Deletion/Addition 12.Construction site Bulldozer’s location Context Location 13.Farm Pickup truck’s door color Focal object Property change 14.Farm Front tractor’s prow Focal object Deletion/Addition 15.Farm Size of loads on the front tractor Focal object Form change 16.Farm Height of the background field Context Form change 17.Farm Airplane’s location Context Location 18.Farm Background barn’s location Context Location 19.Harbor Front steamship’s pedal color Focal object Property change 20.Harbor Logo of the front tag boat Focal object Deletion/Addition 21.Harbor Front boat’s shape of window Focal object Form change 22.Harbor Location of church steeple Context Deletion/Addition 23.Harbor Color of water Context Form change 24.Harbor Ferry’s location Context Location 25.Town Front track’s color Focal Object Property change 26.Town Front bicycle’s wheel Focal object Deletion/Addition 27.Town Front car’s wheel shape Focal object Form change 28.Town Shape of the background building Context Deletion/Addition 29.Town Shape of the sidewalk Context Form change 30.Town Track’s location Context Location 398T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006) Appendix B. Types of Scenes and Changes of the Stimulus Set Used in Experiments 2 and 3 Scenes Changes in the Scene Change Category Subcategory Airport Front plane’s color Focal object Attributes Helicopter’s propeller Focal object Attributes Passenger plane (1)’s logo Focal object Attributes Passenger plane (2)’s number of windows Focal object Attributes Passenger plane (1)’s landing gear Focal object Attributes Passenger plane (1)’s flight course Context Movement Small plane’s flight course Context Movement Passenger plane’s location (2)Context Location Location of helicopter Context Location Shape of a control tower Context Background Shape of a light pole Context Background Construction site Backhoe’s shape Focal object Attributes Forklift truck’s shovel shape Focal object Attributes Forklift truck’s window shape Focal object Attributes Bulldozer’s color Focal object Attributes Bulldozer’s serial number Focal object Attributes Bulldozer’s speed Context Movement Forklift truck’s speed Context Movement Bulldozer’s location Context Location Forklift truck’s location Context Location Number of the construction frame Context Background Shape of the ground Context Background American harbor Tag boat’s lifesaver color Focal object Attributes Tag boat’s flag color Focal object Attributes Tag boat’s number logo Focal object Attributes Tag boat’s lifeboat Focal object Attributes Cruiser’s lifesaver color Focal object Attributes Tag boat’s speed Context Movement Cruiser’s speed Context Movement White boat’s location Context Location Cruiser’s location Context Location Church’s location Context Background Shape of a lighthouse Context Background American farm Air balloon’s basket color Focal object Attributes Tractor (1)’s parts Focal object Attributes Tractor (2)’s number of plows Focal object Attributes Tractor (1)’s exhaust pipe Focal object Attributes Truck in the barn Focal object Attributes Tractor (1)’s speed Context Movement Tractor (2)’s speed Context Movement Air balloon’s location Context Location Pickup truck’s location Context Location Shape of houses Context Background Clouds Context Background American town Limo’s color Focal object Attributes Limo’s shape Focal object Attributes Bleu van’s window Focal object Attributes T. Masuda, R. E. Nisbett/Cognitive Science30(2006)399 Scenes Changes in the Scene Change Category Subcategory Red car’s shape Focal object Attributes Shape of a red car’s wheel Focal object Attributes Blue car’s speed Context Movement Silver car’s speed Context Movement Red car’s location Context Location Limo’s location Context Location Shape of the middle building Context Background Shape of the left building Context Background Japanese farm Tractor (2) driver’s clothes Focal object Attributes Tractor (1) driver’s helmet Focal object Attributes Number of loads on the tractor (2)Focal object Attributes Tractor (1)’s color Focal object Attributes Red tractor’s parts Focal object Attributes Tractor (1)’s speed Context Movement Tractor (2)’s speed Context Movement Red tractor’s location Context Location Tractor (2)’s location Context Location Shape of houses Context Background Clouds Context Background Japanese town Postal car’s symbol Focal object Attributes Cleaning car’s back parts Focal object Attributes Police car’s shape Focal object Attributes Police car’s logo Focal object Attributes Police car’s parts Focal object Attributes Postal car’s location Context Movement Cleaning car’s location Context Movement Green plane’s location Context Location Postal car’s original location Context Location Shape of background buildings Context Background Electric lines Context Background 后现代消费:青少年娱乐亚文化及其发生 钟一彪 摘要:青少年娱乐亚文化反映了青少年消费集体无意识下的青春偶像崇拜与他们崇尚公平重视参与中的感觉主义及反叛权威与传统中的怀疑迷茫倾向。为防止青少年娱乐亚文化成为反文化,需要改变文化泛市场化、信息的缺德传播和道德教育的形式化状况。 关键词:青少年娱乐亚文化价值动向 “追星族”、“模仿秀”、“超女”、“恶搞”……各种形式层出不穷,以至于让人应接不暇。这是中国青少年娱乐文化的现实状况,大多数人对此也习以为常。然而,2006年8月10日《光明日报》主办的“防止网络恶搞成风专家座谈会”却像一颗重磅炸弹,引起了社会各界对青少年娱乐文化现象的关注。人们纷纷追问:青少年娱乐文化到底发生了什么问题?这些问题产生的缘由是什么?青少年娱乐文化为什么缺乏一个必要的伦理底线?对此,本文将从社会文化与价值的角度进行一些分析。 一、青少年娱乐亚文化及其向反文化转变的可能 在日常生活中,人们常用“文化”来形容艺术的高雅与精致,比如,认为古典音乐爱好者是“有文化”的,而追求流行音乐则被说成“没文化”。但是,文化在社会学意义上往往被定义为人类群体或社会的共享成果,这些共有产物不仅包括价值观、语言、知识,而且包括物质对象(戴维·波谱诺,1999)。在文化的整体社会层面上,青少年娱乐活动只能被称为“亚文化”。所谓亚文化,是不同于主文化的仅为社会上一部分人所接受或成为某一社会群体特有的文化。亚文化一般不与主文化相抵触或对抗(郑杭生,2003)。 作为一种亚文化,青少年娱乐文化表现出几个重要的特征:(1)群体共享性。青少年娱乐亚文化作为一种文化现象,必须为青少年所共享。只是一个人所喜欢的东西,最多只能被称作兴趣爱好,只有具备一定数量的共同爱好者,才能表现为一定的文化现象。青少年娱乐亚文化为青少年群体所共享,因为他们具有生理上的类似性,都具有青少年的基本需求。所以,当一种娱乐形式在一些青少年中 浅谈电视剧艺术的大众文化属性 【摘要】电视文化是一种相当复杂的文化形态,既有文化的意识形态性、审美性,又有商品的物质性、消费性;既有强制性、操纵性,又有迎合性、对抗性;既有同质性,又有多元性;既有类型性,又有创造性;既有娱乐性功能,又有教化功能。电视文化本身已经成为一种跨学科的文化形态,涉及到的领域已远远不是传统的文化艺术所能涵盖的,但是却掩盖不了一个重要属性——大众文化属性。电视剧艺术作为电视文化的一个分类已经成为其重要组成部分,因此也一脉相承了电视文化的属性。以往传统上大众文化可以给其下这么一个定义,即从欣赏主体出发,从受众的接收品味和受众的阶层出发。在当代市场经济以及文化全球化的新的历史语境下,已经形成了一个新的大众文化观。笔者将对中国电视剧的大众文化属性所包含的社会功能性做一个详细的论述。 【关键词】大众文化道德电视剧 我国电视文化的历史始于20世纪中期。虽然晚于英国、美国、日本等发达国家,但在改革开放以后却获得了长足的发展。尤其是90年代以来,在经济和科技两个高速运转的车轮的驱动下,不仅在传播内容、传播形式、传播技术上,而且在传播理念与文化理念上都发生了前所未有的变化。 电视剧在其艺术层面上可以从两方面来理解。其一,电视剧是为大众所创作的艺术,它要适应大众的理解力和接受力。其二,当前对大众艺术的认定是从机器生产、成批量生产的工业化方式来进行的,电视剧从整体上看有一定的工业生产性质。 另外电视剧遵循大众文化讲故事的传统。对电视剧而言,故事性的要求是第一位的。这一点和电影有明显区别。从观众出发,我国的观众趋向于情节的欣赏,离开了情节也就失去了观众编剧中心说和导演中心说。由于故事性是电视剧成功的保证,所以一方认为编剧对电视剧更有发言权。我国大众艺术的欣赏传统之中,不仅要求故事的曲折复杂,而且要求叙事的圆满性。电视剧的最终结局是以圆满性以实现感动为结果的,因此电视剧也是以情感人的艺术。大众艺术中的情感要有一个约定俗成的标准。要让剧中人有正确的情感分寸,有合理性的解释,违背基本道德的情感,就会引起观众的反感。 中国的文化在其道德性的表达上有其独特的重点,同样在电视剧艺术上可以归纳出三个特点——英雄化的道德、传统道德、好汉情结。 中国电视剧的英雄道德主要是体现为一种舍己救人、将国家利益放在首位不惜舍去自己姓名的大无畏精神。这种道德体现是与中国文化本身的特点以及整个中国历史社会政治环境所不能分离的。在80年代左右,中小学的道德教育体系是提倡学习赖宁、学习雷锋,班级的墙上往往贴的都是董存瑞、黄继光的海报,保卫祖国、保护国家财产是高于生命的,并且中国式的英雄往往都是无任何品质上和性格上的瑕疵,这是与现实所背离的。中国人历来提倡“诗以言志,文以载 网络语言文化透析及其语言规范标准 江西农业大学肖崇藻 2010年11月10日,网络语“给力”一词登上了《人民日报》头版头条,网友惊呼“太给力了”。在高考作文中也出现神马、伤不起、有木有等网络语言。这类语言的出现与传播主要寄生于网络人群,聊天里经常能出现“恐龙、美眉、霉女、青蛙”等网络语言。 网络语言是伴随着网络的发展而新兴的一种有别于传统平面媒介的语言形式。它以简洁生动的形式,一诞生就得到了广大网友的偏爱,发展神速。久而久之,网络语言就形成特定语言了。 在网络语言风靡全国的浪潮中, 一场关于网络语言是忧是喜的争论一直没有停息。一些语文教师认为,网络语言冲击、解构和颠覆了既有的语言规则,与传统语言文字相比,网络语言大量地使用缩写、错字、别字,显得很不规范。但也有不少人对网络语言的立法禁用嗤之以鼻,认为这有些矫枉过正。汉语有其广博的包容性,网络语言带来的冲击不仅不会触及汉语根本,反而会为其注入新的活力,更加丰富汉语的语言词汇。 笔者认为:首先,认识到网络语言的两面性、内在矛盾是语言学者必须有的哲学素养,认识到语言的发展是由于社会发展因其内部体系和功能的矛盾而导致的语言变化,也是我们对待文化的首要态度。语言不仅反映语言本身,更反映了一种文化,也是一种特殊的文化现象。伴随着改革开放思想的解放、科技进步、 市场经济发展、创新的逐步展现引发的创新形态、社会形态变革及其带来的社会大众道德观念、爱好趣味、价值审美等变化,出现了网络语言这一语言文化现象,这个文化现象我们称之为“草根文化”。草根文化是属于一种在一定时期内由一些特殊的群体引发的一种特殊的文化潮流现象,它实际是一种“副文化、亚文化”现象。它具有平民文化的特质,属于一种没有特定规律和标准可循的社会文化现象,是一种动态的、可变的文化。 再次,哲学家黑格尔曾说:“凡是现实的就是合理的,凡是合理的就是现实的。”我们应该承认这一文化现象,在文化领域中既要鼓励语言文化的创新也要加强语言规范工作。 具有革命意义的创新性是网络语言最大的特点,在可以充分发挥想象力和创造性的最自由的空间里能够最大限度地反映出每个人在语言上的创造力,对于形成独立、自由、创新的学术氛围和创新型国家都有着巨大的推动作用。所以我们要积极地鼓励语言的创新,引导网络语言的发展,而不是一味打压、禁止。 同时,规范的语言文化也是精神文明建设之要,是文化创新的时代要求,是我们促进国际文化交流、加强文化传播的必备条件。现代各种语言的标准语的功能日益扩大,为了适应这一趋势,政府应制定正确的语言规范政策,因势利导,以维持语言的统一,保持语言的纯洁和健康。国家语言改革工作委员会一位负责人表示对网络语言要有一个比较好的了解和认识,然后才能决定何时规范,怎样规范。词典室助理研究员张铁文认为:“网络 2 组织变革与组织文化 本章纲要 本章共分三节,属于第三篇组织的重点章节,历年考题较多,要求考生在理解的前提下准确掌握本章内容。第一节对组织变革的动因、类型、目标和内容进行介绍;第二节是本章重点章节,要求考生给予更多的关注;第三节介绍了组织文化的概念、特征、功能和形成。 本章知识脉络结构图 重点知识梳理 一、组织变革的含义 组织根据内外环境的变化,即使对组织中的要素进行结构性变革,以适应未来组织发展的要求。(3C 力量—顾客、竞争、变革,变革最为重要) 组织变革与组织文化 组织变革的一般规律 管理组织变革 组织文化及其发展 ?组织变革动因 ?组织变革类型 ?组织变革目标 ?组织变革内容 ?组织变革过程与程序 ?组织变革阻力及其管理 ?组织变革中的压力及 其管理 ?组织冲突及其管理 ?组织文化的概念 ?组织文化的特征 ?组织文化的结构内容 ?组织文化的功能、塑造 二、组织变革的动因 (1)外部环境因素:①整个宏观社会经济环境的变化;②科技进步的影响;③资源变化的影响;④竞争观念的改变。 (2)内部环境因素:①组织机构适时调整的要求;②保障信息畅通的要求;③克服组织低效率的要求;④快速决策的要求;⑤提高组织整体管理水平的要求。 三、组织变革的类型 (1)战略性变革。组织对其长期发展战略或使命所作的变革; (2)结构性变革。组织需要根据环境的变化适时对组织的结构进行变革并重新在组织中进行权利和责任分配,使组织变得更为柔性灵活、易于合作。 (3)流程主导性变革。组织紧密围绕其关键目标和核心能力,充分应用现代信息技术对业务流程进行重新构造; (4)以人为中心的变革。组织必须通过对员工的培训、教育等引导,使他们能够在观念、态度和行为方面与组织保持一致。组织中人的因素最为重要,组织若不能改变人的观和态度,组织变革就无从谈起。 四、组织变革的目标 (1)提高组织的环境适应性;(2)提高管理者的环境适应性;(3)提高员工的环境适应性。 五、组织变革的内容 (1)人员的变革。人员的变革是指员工在态度,技能、期望、认知和行为上的改变。(2)结构的变革。权利关系、集权程度、职务与工作再设计等其他结构参数的变化。(3)技术与任务的变革。包括对作业流程与方法的重新设计、修正和组合,包括更换机器设备,采用新工艺、新技术和新方法等。 六、组织变革的程序 (1)通过组织诊断,发现变革征兆;(2)分析变革因素,制定改革方案;(3)选择正确方案,实施变革计划;(4)评价变革效果,及时进行反馈。 七、组织变革中的压力 中国传统文化近代以来发生了哪些变化 摘要:中国传统文化是中华文明演化而汇集成的一种反映民族特质和风貌的民族文化,是民族历史上各种思想文化、观念形态的总体表征,是指居住在中国地域内的中华民族及其祖先所创造的、为中华民族世世代代所继承发展的、具有鲜明民族特色的、历史悠久、内涵博大精深、传统优良的文化。它是中华民族几千年文明的结晶。然而,随着近代中国社会所发生的历史性剧变,中国传统文化面临越来越多外来文化的挑战,它不再是中国人所接触的唯一文化。从鸦片战争英国打开中国国门,到如今全球经济一体化进程迅猛加快,经济上的全球化势必造成中国传统文化在近代发生改变,而它到底发生了哪些改变,人们又是如何去适应这种改变,中国传统文化如何在不失其内涵的情况下更好的适应时代的发展立足于世界文化之林将是本文讨论的重点。 中国历史悠久,在古代长达一千多年的时间里,中国文化一直遥遥领先于世界,在封建统治的时代里,整个国家经济,政治,科技相对于世界上任何地区都是值得骄傲的,这也使中国人对自己传统文化的认同感极强。也正是这种认同感和优越感让中国一度孤立于世界,然而,最终,这一千多年来沉淀下来的优势被西方一次工业革命彻底赶超,当英国的使臣来到大清国试图劝说乾隆皇帝放宽港口贸易,与英通商时,得到的却是一脸的不屑和拒绝,“天朝物产丰富,无所不有,原不藉外夷”一句话暴露了当时中国的闭塞性,也注定着清朝的灭亡。同时,几千年来的文化底蕴也很难让中国人快速的转变,所以19世纪的历次改革失败也无不与这有关,然而,中国人终究还是醒了,面对列强的侵略,他们一方面感叹西方文明的强大,一方面也开始反思自己,中国是该改革了。 改革的步伐是艰难的,当辛亥革命摈除了譬如缠足,留辫子,跪拜礼等陋习,推翻了清政府的统治,这为新文化的传播和发展都立下了不可磨灭的功劳,民主共和观念深入人心,这为中国政治最终的胜利奠定了思想基础,这是中国传统文化在近代的一次大变革。 新中国成立后,人们沉浸在革命胜利的喜悦之中,一直到文化大革命期间,中国文化由于与外部隔绝并没有太大的改变,然而文化大革命却是对中国传统文化的一次严重摧毁,且不说政治层面的迫害对我国经济,政治产生的恶劣影响, 在对待传统文化的态度上采取了极端的态度,在文革十年期间内,很多文物被摧毁,诸如孔子这样的伟大思想家和诸葛亮这样历史杰出人物,都被极端的扭曲化,这是对历史的不尊重,更是在新中国发展阶段各种矛盾突出的情况下对传统文化的一次挑战,这并不是一种正常的现象,是一种纯粹的破坏,许多历史古迹被破坏,这对中国传统文化来说是一场灾难。 后来,改革开放的序幕在中国拉开,经济建设迅猛发展,我们在大量吸收外来资金的情况下也在潜移默化的受外来文化的影响,尤其是西方文化,在享受物质文 文化大繁荣背景下的国学热现象的透析 法学院10级1班学号:1002010119 摘要:国学作为传统文化的载体,在数千年的发展中,传承着我们民族 的优秀思想和文化传统。而现在国学热提示着中华民族自我意识的觉醒,体现了民族自尊与自信的高扬,开启了民族文化的自觉。当然,对国学也同样有个扬弃的问题。取其精华,去其糟粕,以积极的态度对待国学热的讨论,是今天我们应有的正确态度。 关键词:国学国学热传统文化 最近几年,大家都在谈国学,这已经成了一种趋势。比如中国人民大学率先成立了国学院,很多高校也成立了国学研究机构,或教学组织,厦门大学则于2006年恢复了创建于1926年的国学院,《光明日报》也开设了《国学》专版……我们称之为“国学热”。在当今国学热潮下,许许多多的家长把孩子送到各种各样的国学班里,背诵“人之初、性本善”,背诵“赵钱孙李、周吴郑王”,穿汉服、学经典……,而在目前文化大繁荣的背景之下出现国学热现象,我们则应该理性的思考其出现的原因并且应该坚持辩证的观点来正确的对待。 我认为当前“国学热”现象主要以下有几个方面的原因: 第一是我国经济的持续发展引发了国学热。改革开放以来的30多年间,人们的思想走出了过去封闭保守的僵化状态,国家的工作重心由以阶级斗争为纲转变为以经济建设为中心,由计划经济走向市场经济,在各个方面取得了举世瞩目的成就。随着中国经济的发展以及与国际社会交往的日益频繁,中国人越来越迫切需要了解自己民族的历史,越来越需要展现中华民族文化中所具有的独特价值的东西,这就激发了中国人复兴传统文化的强烈愿望。当人们试图从传统文化中寻找能代表中华民族的精神和象征时,挖掘传统文化及儒家思想中有价值、有益的思想资源就成为顺其自然的事了,这也是我们这个民族文化自信和文化自觉的一种表现。这或许就是当今“国学热”产生的一个原因。 第二是我们党和政府的宣传和鼓励。近年来我国政府一直提倡的以德治国、依法治国、以人为本、构建和谐社会、和谐世界、八荣八耻、社会主义荣辱观等。而国学热现象与之有密切的联系。一方面因为这些思想本身就是来源于中国传统文化,是中国传统文化中固有的内容。另一方面是因为适应国际竞争的需要。当代国际竞争的实质是以经济和科技为基础的综合国力的较量,而综合国力则主要包括了国家的硬实力和软实力。这里的软实力则主要是文化软实力。文化越来越成为衡量一个国家综合实力强弱的重要尺度之一, 文化的力量, 深深熔铸在民族 网络用语的文化现象分析 摘要:网络语言作为一种新兴文化,及时的反映了当今社会群体的文化特点。那么它表现出了我们当今社会什么样的文化心理或是社会心理。这种表现是否与我们当代的生力军———青年一代有非常重要的关系。我们试从文化语言学的角度和伯明翰受众理论的基础上对网络语言的文化进行剖析。 关键词:网络语言社会现象大众文化 一、网络语言是一种特殊的社会现象 (一)语言与社会。德国的洪堡特认为,实际上,语言只有在社会中才能发展。房德里耶斯在《语言———历史的语言学引论》中明确提出,“语言是一种社会现象,语言是结合社会的最强有力的纽带,它的发展依赖于社会集团的存在。”拉法各耶曾经指出:“一种语言不能跟他的社会环境隔离,正如一种植物不能离开它的气象环境。”而网络语言也是在社会的环境中生存的。 语言是特殊的社会现象,是人类作为必不可少的思维工具和最重要的交际工具来使用的音义结合的符号系统。网络语言是以因特网为媒介而产生的一种新的社会方言的变体。之所以这么说,是因为在网络语言中,它不仅将口语和书面语融合,将地域方言和社会方言融合,而且还将各种无法以汉字表示的情态,以一定的形式在电脑屏幕上表达出来,形成了网络语言特有的形式和风格,这些都与计算机网络的发展有着密不可分的关系,并与传统的语言形式都有较大差异。从根源来说,文化坐落于社会大系统中,无时无刻不受外部社会环境的影响,从社会系统的环境因素看,伯明翰学派的“大众文化”具有情境化特征,它是在具体的社会实践中产生和发展起来的。这样印证了网络用语文化现象并非无风起浪,而是产生在无处不在的社会环境之中,是一种特殊的社会现象。如果说社会实践是文化研究的活水源头,而社会实践又处于不断发展过程中,那么文化研究就应该随着社会实践而不断更新,用贴近于生活和民众的文化理念正视并解答新的社会问题。 网络中词义的变化与网络自身的特点及当代生活息息相关。 网络就是一个巨大的信息集散地,全世界的信息都以极快的速度在网上传播,新信息、新资讯铺天盖地的席卷而来。因而网络用语也以日新月异之貌,呈现于大众的面前,不仅如此,在各民族文化相互交流日益频繁、世界各国文化相互冲击的环境下,网络语言无疑也受到了影响,就那其语言本身来说就已经表现出一定的中外融合性。尤其是英语和日语对中国网络语言的影响更大一些。比如:“……ing”这个词语,学过英语的人都知道这是表示“正在进行”的时态,因此网民就将其运用于网络语言中,例如:吃饭ing、睡觉ing……这都说明一个问题,在刚开始只是文化接触的基础上,各国语言相互之间也将会有一定的影响。这在我们日常生活中最早表现在外来词的使用中,还没有涉及到语法和语音,但是随着时间的推移,各国的语音和语法之间会不会有产生一定的影响,这就不得而知了。但在网络中它已初步表现出了一定的融合性———尽管它还并不规范。按照帕森斯的社会结构理论,自然、文化、政治、经济在社会大系统中相互联系、相互制约,并处于不变变动的过程,结构不是封闭的,而是开放的。从社会系统的结构看,伯明翰学派的大众文化也是开放性的文化,表现在呈现方式上以学科交叉为其特征,发展趋势上以文化变迁为其特征。 二、网络语言是当代潮流文化的镜象折射 论网络青年亚文化的研究现状及反思 【摘要】网络新媒体、青年亚文化的迅猛发展,影响着现在青年群体的人生观和价值观,这些文化以特殊的表达方式潜移默化的推进主流意识形态建设的发展。当代青年亚文化有着娱乐性和批判性的特点,这种特点的存在,也体现了青年群体对事物有多元化的诉求和自身复杂的心态,青年群体的外在表现是在狂欢中放逐自己,它的内在精神确是在批判中构建,这种形式不利于青年群体的发展,为了改变这种现状,应该建立多元的引导方法和分级的治理办法。 【关键词】网络空间;青年亚文化;主流文化 一、在狂欢中放逐是网络空间青年亚文化的外在气质 (一)青年在娱乐狂欢中逃离主流文化的规律。新媒体环境下,青年亚文化渗入到文化结构中,以它独特的风格形成了文化形式。青年亚文化真实反映了这些群体对文化的诉求和态度,使主流文化与青年亚文化之间产生了复杂的关系,青年亚文化在很大程度上影响着主流文化。在现实世界中,面对的压力有很多,学习、工作、生活等现实压力无处不在,这些压力让他们变得焦虑不安。但是在虚拟的网络世界就不同了,青年都罩着一层面具,没人会摘下他们的面具,在网络世界里,青年是自由的,他们隐藏在面具后,毫无顾忌的在论坛、贴吧等平台发表这自己的言论,利用图片,影 像等工具进行着网络文本的传播,他们制造网络热点和跟着网络热点发表自己的看法,达到集体狂欢的效果。他们在网络世界里自由的翱翔,成为现实生活中自己不敢成为的人。用文字释放自己的不满,得到了心理上的安慰,也发泄了自己的情感。他们在自娱娱人的过程里放纵自己,躲避着社会的规则,逃离现实社会的压力。 (二)青年在娱乐狂欢中不断强化自我身份认同。青年群体都有一个特点,就是乐于尝试新事物,有强大的探索欲。但是在尝试新鲜事物的过程中,会对自己的行为产生是否正确的迷茫感,他们需要别人的肯定,而其他人认可他们的行为会对他们产生积极效应,强化他们对自己身份的认同。有一种说法是:物以类聚,人以群分。青年亚文化和这个类似,是一群兴趣或其他方面有共鸣的青年自发聚集,形成的一种文化氛围。在新媒体的环境下,青年将自己的趣味来界定自己的文化空间。在网络的虚拟世界中,他们不断寻找和自己兴趣相投的人,和他们交流情感,最终所有人形成一个相互认同的情感共同体。 二、在批判中建构是网络青年亚文化的内在精神 当代青年亚文化的批判建构精神从未陨落。这种批判精神只是变换了风格,隐藏在青年亚文化狂欢的现象之下,让人们发现不了。青年亚文化隐藏着青年群体的多元化价值诉求,青年亚文化从来不是年轻人的游戏,是一种独具一格的 进入新世纪,李白研究发展到新的历史阶段,专题探索正向纵深掘进。在近几年李白研究的众多成果中,何念龙研究员的专著《李白文化现象论》[1]比较突出。作为国家社会科学基金项目研究成果,该书以宽广的学术视界、新致的思维路向和包容性理论建构而引人关注,标示着该研究领域的重要进展,其学术探索和研究特色主要表现在三个方面。 一、从思维论着眼,精心创建新的理论架构 该著扎实厚重,内容丰富,洋洋44万字,共分5章25节,以建构论、特质论、再塑论、比较论、本质论等为结构框架维度,各自相对独立又密切关联。该著着眼于学术思维路向的变更,在学界首次使用“李白文化现象”理论话语并加以全面深入阐解。作者认为,李白其人其诗及历代相关的史传记载、诗文评论、文艺作品和故事传说,构成了一个多姿多彩、长盛不衰的“文化特异景观”。其生前社会轰动效应和死后巨大深远影响无人能与比肩,历代士人群体和普通民众不断地对李白进行解读、评论和再塑,在中国古代经典作家接受史上空前绝后而成为独特的文化现象。李白文化现象的基本内涵包括作者本人、作品文本、巨大影响三个基本建构维度,具有独特性、雅俗共赏性和历史积淀性三个主要特征。这一现象的成因主要源自于其人其诗本身特异性、盛唐时期的精神孕育、士人阶层的心理诉求。这一现象的本质和核心是“李白文化精神”,即高度的人文关怀精神、极度的自由狂放精神、强烈的反权贵精神、淋漓酣畅的诗酒精神[2](382)。作者对此特异现象的内涵构成、基本特征、生成机制进行了细致深入的阐析,使读者对于这一现象有了整体的理解和把握。作者还以“三型李白”论作为透析此一现象的“锁钥”,力求对“李白文化现象”做出深刻的解读。 “李白文化现象”命题和“三型李白”论,是该书对李白研究所提出的创意性的理论架构和全新的学术话语。回顾已往李白研究,基本上一直沿袭既定套路和阐释传统,即关于家世出身、生平经历、思想精神、交游行踪、艺术风格、创作特色、历史影响等传统研究内容和单向性、分解式研治思维,仿照史料汇编、作品集注、诗文系年、史实考证、文本诠释等惯常路数。从思维论视角来看,作者经过长期学术积累和多年不懈探索,以卓然独立学术姿态,锐意创新,突破了该研究领域那种单维度、线性型、平面化的思维定势和操作惯性,致力于系统集成的逻辑建构,使对李白的研究更具完整性和立体感。在李白问题上,将宏观观照与微观解析、历时性审视与共时性剖析相结合,高屋建瓴,整体在握,显示了开放性和生发性特征,强化了系统性和立体化色彩,具有很强现代学术品格。这种理论构架,为李白研究的拓展和深化奠定了坚实的基础,有利于更全面、更深刻地研究李白。 二、从重点论着力,深度透析两个重要问题 李白是超迈绝伦的特殊性存在,对其现象史问题研究需要将整体把握与重点阐解结合起来。作者突出重点而深度阐析,紧紧抓住两个最重要问题, Vol.33No.11 Nov.2012 第33卷第11期2012年11月 赤峰学院学报(汉文哲学社会科学版) Journal of Chifeng University(Soc.Sci) 李白研究领域的新开拓 —— —何念龙研究员新著《李白文化现象论》读后 谈晓明 (江汉大学人文学院,湖北武汉430056) 摘要:“李白文化现象”和“三型李白”论(“历史原型李白”、“诗艺造型李白”、“传说塑型李白”),是《李白文化现象论》对李白研究所提出的创意性的理论架构和全新的学术话语。《李白文化现象论》突破了该研究领域那种单维度、线性型、平面化的思维定势和操作惯性,有助于探索解决一些悬而未决的迷踪谜案,从而为李白研究的深化奠定了的基础。 关键词:李白;李白文化现象;三型李白论 中图分类号:I207.22文献标识码:A文章编号:1673-2596(2012)11-0098-02 98 -- 中国传统文化的过去和传承以及发展 高二(1)班张慧 提要:所谓传统文化,就是受特定文化类型中价值系统的影响,经过长期历史 积淀而逐渐形成的,为全民族大多数人所认同的思想和行为方式上的难以移易的心理和行为习惯。近代以来,中国传统文化发生了巨大的变化。对于几千年来维系中华民族精华之源泉,深蕴着丰富营养成分的中国传统文化,如何才能在经济全球化导致的文化全球化的今天得到更好地传承和发展,笔者认为只有历史辩证地正视中国传统文化,重视传统文化的理论研究、保护传统文化的物质载体、重构传统文化的价值体系、采用不同的媒介对传统文化进行传播,才能更好地传承和发展中国传统文化。 关键词:中国传统文化;过去;发展;传承 传统文化是指在长期的历史发展过程中形成和发展起来,保留在每一个民族中间具有稳定形态的文化。中国传统文化是指以华夏民族为主流的多元文化在长期的历史发展过程中融合、形成、发展起来,具有稳定形态的中国文化,包括思想观念、思维方式、价值取向、道德情操、生活方式、礼仪制度、风俗习惯、宗教信仰、文学艺术、教育科技等诸多层面的丰富内容。近百年来,国人对待中国传统文化的态度是冰火两重天。上世纪两次大的文化运动——五四运动、文化大革命,使中国传统文化遭到灭顶之灾,而尤其可悲的是使中国人几千年形成的传统的思想观念、价值取向、道德情操难以为继,使新一代的中国人出现了信仰危机、价值危机、道德危机,导致民族精神的衰落。改革开放以来,随着人们思想的解放,冷静的反思;随着中国国力的强盛,民族自尊心、自信心的恢复,研究和发展中国传统文化成为当下思想文化界一道众所瞩目的风景线。由政府到学界,由国内到国外,国学热不断升温。如,在《百家讲坛》阎崇年讲清帝、刘心武讲红楼、易中天讲三国、王立群讲史记、于丹讲论语;《光明日报》专门开设了国学版,中文搜索引擎百度开设了“国学频道”,新浪网高调推出乾元国学博客圈,政府举办了“俄罗斯‘中国年’”、“德国‘中国年’”,在各个国家开设孔子学堂,等等。这一冷一热带给我们很多思索:我们应该如何看待中国传统文化?应该采取怎样的方式传承和发展中国传统文化?笔者简要地探讨如何对待中国传统文化,并对传统文化的现代传承方式作了思考。 一、中国传统文化的过去和传统社会 中国传统文化是个庞大的有机体,可以从多方面去解读,加上解读者视角和认识的差异,众说纷纭、莫衷一是乃是正常现象。愚见以为,从社会变迁的角度看,陈寅恪关于中国传统文化的见解很值得注意。他的见解概括起来有这么几个要点: 1.中国文化可分为制度层面和非制度层面。“自晋至今,言中国之思想,可以儒释道三教代表之……故两千年来华夏民族所受儒家学说之影响最深最巨者, 2009年6月 第6卷第6期 Journal of Hubei University of Economics(Humanities and Social Sciences) 湖北经济学院学报(人文社会科学版) Jun.2009Vol.6No.6 从原始宗教文化的起源即原始社会人类敬畏大自然、崇拜大自然的祭祀活动和原始人维护男女有别、扶老携幼的天然人伦秩序的需要以及祖先“灵魂不灭”的思想看,礼仪的本质是“敬”。远古时代人们之间的关系比较单一,为了生存要形成一定规模的群体才能适应严酷的生存环境,在共同的劳动、共同的生活中,思想、情感和行为上必须步调一致,形成良好的协作关系,这种关系使人们在平时的交往和劳作中必须互相平等互相尊敬互相爱护,这就形成了原始文化现象中的礼仪文化。在原始社会中、晚期(约旧石器时期)出现了早期礼仪。例如,生活在距今约1.8万年前的北京周口店山顶洞人,他们用穿孔的兽齿、石珠作为装饰品,挂在脖子上来装扮自己。山顶洞人在去世的族人身旁撒放赤铁矿粉,举行原始宗教仪式,这是迄今为止在中国发现的最早的葬仪。同时原始人已经懂得尊卑有序,例如在半坡遗址和仰韶文化时期,发现了生活距今约五千年前的半坡村人的公共墓地。墓地中坑位排列有序,死者的身份有所区别,有带殉葬品的仰身葬,还有无殉葬品的俯身葬等,从某种意义上说,早期礼仪包含原始社会人类生活的若干准则,又是原始社会宗教信仰的产物。另外,从“神农尝百草”、“舜躬耕畎亩”、氏族首领“身执耒臿,以民为先”等故事,都反映了原始礼仪文化“敬”的内涵。 一、从原始宗教文化的起源———崇拜大自然的祭祀活动,说明礼仪的本质是“敬” 从繁体字“禮”的结构来看,左边是“示”字,意为祭祀敬神,右边是祭物,表示把盛满祭物的祭具摆放在祭台上,献给神灵以求福佑。据《辞海》注释:“礼”的本意为敬神。这是因为在原始社会,生产力水平极其低下,人类处于原始、蒙昧的状态,对日月、星辰、风雨、雷电、海啸、山崩、地裂等自然现象无法理解,由此对自然界产生了一种神秘感和敬畏感,从而形成了对大自然的崇拜,并按人的形象想象出各种神灵作为崇拜的偶像。例如照耀大地的太阳是神,风有风神,河有河神……因此,他们敬畏“天神”,祭祀“天神”。同时,由于原始人对自身的梦幻现象无法解释,产生了“灵魂不死”的观念,进而产生了对民族祖先的崇拜。自然力量和民族祖先一直是原始社会最主要的两个崇拜对象。对两者的崇拜,主要以祭祀的方式表现出来。人类通过祭祀活动,表达对神和祖先的敬仰、崇拜,期望人类的虔诚能感化、影响神灵和祖先,从而得到力量和保护。在他们祭祀天地神明以求风调雨顺、祭祀祖先以求多赐福少降灾的过程中,原始人虔诚地向这些“神灵”和“祖先”打恭跪拜,表示崇拜、祈祷、致福。祭祀活动日益频繁,原始人的“礼”便产生了。已有3800年上下之久的武夷山景区北部边角、中部九曲溪两岸的悬棺这个独特的葬俗就是古闽人留下的“闽”葬俗文化。在武夷山千仞绝壁上发现的悬棺的年代(大约在夏代之前),经碳14断代测定,一号船棺距今3840年,二号船棺距今3450年。悬棺葬这种方式是把死者棺木放置在悬崖绝壁上,保护死者死后不受到任何侵犯,让死者的灵魂继续保护他的子孙后代,悬棺葬礼俗表现的是孝敬、祖先崇拜和灵魂不灭的观念。整个丧葬仪式体现的对已故先人的崇敬“礼”是如此的天然和虔诚。以此也可以完全诠释古闽人丧葬礼俗体现的孝道、对祖先崇拜、先人死后灵魂不灭的天然的“敬”的礼文化思想内涵。从原始礼仪文化的最初“根”的开始就是敬自然、敬民族祖先,所以礼仪的本质是“敬”。 二、维持群体生活需要的“天然人伦秩序”,是礼仪本质“敬”产生的最原始动力 原始人类为了生存与发展,在与大自然抗争的同时,也要处理好人与人、部落与部落的内部关系。而在群体的共同生活中天然的存在着一种人伦秩序,那就是:男女有别、老少各异、扶老携幼。这也正是《三字经》第一句“人之初,性本善”的写照。男性和女性是有区别的,在原始社会初期,男性的主要工作是出门去打猎;女性留在部落里生儿育女,操持家务,照顾老人,女性最伟大的是具有繁衍后代的生育能力,因此在原始社会初期(母系氏族社会)这种天然的人伦秩序本能地决定了女性处于领导的地位。这就是男性尊敬女性的思想体现。老少各异、扶老携幼,同样原始人类天然的认识到老人和孩子不同,老人体弱不能出门打猎要瞻仰老人,孩子年龄小需要照顾,在部落里打来的猎物老人和孩子和其他人一样都有同样的一份,在生活的各个方面老人和孩子是同样受尊敬和照顾 从原始文化现象透析礼仪的本质 来玉英 (武夷学院中文系,福建武夷山354300) 摘 要:本篇文章从原始宗教文化的起源、维持群体生活需要的“天然人伦秩序”,原始人类与自然抗争的过程 中相互形成的互助和谐的原始礼仪文化现象,以及原始首领“爱民”、“敬民”的和谐政治思想四个方面的原始文化现象,透析了礼仪的本质是“敬”。目的是通过它来告诉现代人,人与人相互尊敬的思想从原始社会初期就已经存在,而在现代社会,礼貌、礼节的缺失令人堪忧,人们需要相互尊敬、相互友善、相互帮助。本篇文章通过原始文化现象来透析礼仪的本质,对社会现实及和谐社会建设具有一定的借鉴意义。 关键词:原始文化;现象透析;礼仪本质 106·· 先树立一个出发点吧,其实中华五千年灿烂文化,都逃不过“儒释道”三个字。儒家,主讲“仁”、“中庸”;释家,主讲“苦”、“为善”;道家,主讲“悟”、“淡泊”。再通俗一点:儒家玩的就是矫情,释家玩的就是受苦,道家玩的就是缥缈! 下面具体来说。 1.东西方文化传承问题 这个很有特点,不得不提一下,也算是个纲领性质的了。 中国的文化传承明显地起点高,而且门派极多。古时候就有儒家、道家、法家等诸多分支,各家自说各家话,俗称“百家争鸣”。这样导致后人上手很难,更别提超越前人了。这个很容易验证:你见过有哪几个人的学问超过孔子、老子之类的圣贤了?这个就是基础不统一造成的问题,而且由于光一门的入门就比较难,要说掌握就更难了,那么超越前人,就简直快成做梦了。当然,相当牛的人除外。 但是西方的文化就不一样了。他们注重基础,而且讲得很简单,入门极其容易。而且分门别类也不像中国这么复杂:就物理、化学、生物之类的。刚开始都是原子、元素、细胞,基础很统一,也很扎实。这样,学生超过老师就比较容易,学问本身的发展也就更简单了。 此消彼长,西方文化的强盛而且东方文化的没落差不多就这个原因了。 2.东西方文化重心的问题 这个算是上面的补充,但是有必要单独提出来讲讲。 东方文化,更确切地说,东方科学,以五行阴阳而入,讲究天人合一、人与自然和谐发展,而且不去追究最深层次最基本的东西。其实大家一直对东方科学存在误解,觉得他迷信。那是因为我们在以西方的科学思维分析东方的问题。中国看似玄乎的形象,诸如阴阳五行,其实是一个二次抽象的概念。即首先对各个事物进行一次抽象,总结出共性。然后对共性再次抽象,曰阴阳五行、青龙白虎之类。 而西方科学则是以最基本的东西为重心,从原子分子出发,研究事物的本质属性,从而也导致了科技的迅猛发展。 但是问题在于,表面上西方文化很好,人们的生活越来越现代化。但是这是以牺牲环境、牺牲资源为代价的。科技发展得越迅速,付出的代价就越大!仔细想想,我们研究到那么深层次真的有那个必要吗?人们其实只要吃饱饭就差不多了。不过,这个确实是没有办法的事情,只要国家还在、阶级还在、斗争还在。 下面再把重点拉回到对中国人的描述上来。 1.很多人不理解甚至痛恨中国人的形式主义,但是我们还是要比较客观地去看待这个问题。形式,最早来自儒家的礼,当时的国家以礼治天下,也就有了很多形式。我说了,儒家玩的就是矫情,在儒家思想统治了这么多年后,中国人的形式主义也就起来了。坏处我不多说,大家都深有体会,但是好处也是要提的:由礼演化而来的形式,起码从形式上来说是好的,这个配合上中国人的死要面子,有时候就是能起到不可思议的效果。 2.刚才已经说到了中国人死要面子,这个是毋需质疑的。这个来自哪呢?应该也是来自 第31卷第1期 吉首大学学报(社会科学版) 2010年1月Vol.31,No.1 Journal of Jishou University(Social Sciences Edition) J an.2010新媒体环境下青少年亚文化的“新风格化”3 刘怀光,乔丽华 (河南师范大学青少年问题研究中心,河南新乡 453007) 摘 要:青少年亚文化通过一系列符号系统表达自身独特的风格化追求,这种风格化在现代社会与新媒体结缘,新媒体环境下青少年亚文化的表达核心在于价值观的后现代性和社会观中对话语权的争夺,具体表现在个性追求和娱乐精神方面的“新风格化”。在文化意义上,这种“新风格化”与主流文化既存在着矛盾与抵抗,也存在着联系,同时,“新风格化”也在引领着新的主流文化发展的方向。 关键词:新媒体;青少年亚文化;新风格化 中图分类号:D432 文献标识码: A 文章编号: 100724074(2010)0120137204 基金项目:河南省教育厅人文社会科学研究基地项目(20082JD2002) 作者简介:刘怀光(19642),男,河南许昌人,博士,河南师范大学青少年问题研究中心教授。 青少年亚文化的风格从符号意义上来理解就是青少年亚文化表达的一种方式和沟通渠道,是青少年亚文化存在的基础。以青少年为主体所创制和使用的“风格化”彰显出他们青春期生理、心理状况,并在当代社会语境下,以共同的“风格”为基础形成了一种青年亚文化现象。英国伯明翰学派的代表人物之一迪克?赫伯狄格指出青少年亚文化具有的“风格化”是它的“抵抗”方式,它采取的不是激烈和极端的方式,而是较为温和的“协商”,主要体现在审美、休闲、消费等方面,是“富有意味和不拘一格的”。[1](P29)风格(style)是亚文化群体的“第二肌肤”和“图腾”,是“文化认同与社会定位得以协商与表达的方法手段”。[2](P25226)随着科学技术的发展,尤其是现代传媒的发展,新媒体的出现,使青少年亚文化在展现和表达方面有了“新风格化”,这种“新风格化”从一定意义上表现了现代青少年亚文化在社会中存在的文化意义,并充分彰显了青少年亚文化与主流文化的“抵抗性”,也因其新的“风格”而成为未来主流文化的制造者和倡导者。 一、新媒体环境下青少年亚文化的“新风格化” 青少年亚文化主要是由青少年创造、认同并传播,与生活主流文化既相关联又相对独立,它包括思想观念、价值体系和行为方式等。青少年亚文化的目的就是通过符号化的创造,即“风格化”,向人们传达青少年群体特有的意义,而在传达过程中需要借助于旨在进行文化传播与舆论扩散的媒体。随着科学技术的发展,因特网纳入媒体的范畴,于是就出现了“新媒体”这个概念。“新媒体”实际上是一个随历史变迁而不断改变指涉对象的概念。在漫长的历史进程中,人类一直依赖纸质媒介。20世纪60年代,以电波为物理基础的广播和基于图像传播的电影、电视相对于纸面传播,被广泛地称为“新媒体”。到20世纪末,联合国新闻委员提出 3收稿日期:2009211229 浅析“黄色”一词含义历史变迁及中国传统文化反思 黄色代表端庄典雅、荣华、富贵,它给人一种内心平静和对美好生活向往的感觉。黄色在中国最初的含义是明亮和富贵,代表鲜明的个性,沉甸甸的财富,在中国传统文化里居五色之中,是帝王之色,象征着尊贵。五行学说记载黄色中和之色,自然之性,万世不易。《通典》注云:黄者中和美色,黄承天德,最盛淳美,故以尊色为谥也。可见,黄色在中国古代崇高的含义。 到了近代,革命精神和爱国精神使很多爱国人士赋予黄色新含义,而西方肤色种族分类理论的传入也增强了国人对黄色的感知。绝大多数西方科学家援引肤色标准即白种、黄种和黑种将地球人分为三种,它们分别居住在三块大陆,其中黄种人居于亚洲,黄种人观念在19世纪的西方文学中被迅速普及,并通过传教士传到中国。近代中国人在与西方列强的接触和对抗中,对自己黄种的肤色和黄种人的归类逐渐具有了强烈的自我意识,加之德皇威廉二世等有感于日本在经济、军事方面日益强盛的现实威胁,在西方鼓噪黄祸论,又从反面刺激和强化了这一意识,因而为中国传统的尚黄文化,注入了新的时代内涵。而黄种人也逐渐被视为中国人的代名词。 20世纪初,中国在国际上面临着西方列强的侵略,西方列强不但向占用我国的土地资源,还想在思想上将国人控制在他们的魔抓下,因此不断向中国灌输一些与我国传统文化相对抗的东西,其中不乏一些不道德、不能登大雅之堂的东西传入,企图通过思想文化上的侵蚀来摧垮国人的抗争意志,然而这丑陋的目标并未得逞。西方人以肤色将人分为三六九等,而称中国人为黄种人,在西方,黄色本身就具有丑陋、胆小、无能之意思,将中国人称为黄种人本身是想要污蔑、诋毁中国人,然而国人并不吃这一套,反而增加了对黄色一词的民族认同感,凡是提到黄色、黄种等词必然激发其民族、爱国情绪的千层顽浪。因此欧美种族肤色分类理论的传入促使了中国人赋予黄色一词强烈的民族认同感,这甚至使国内掀起尚黄大潮。 民国时期,对黄色的文化尊崇得到进一步延展。国粹派代表刘师培《古代以黄色为重》一文,开篇写道:近代以来,种学大明,称震旦之民为黄种。而征之中国古籍,则五色之中,独崇黄色。他从政治文化角度对当时兴盛的种族和民族革命浪潮的一种独特呼应。1934年,时任广州市长的刘纪文提议定黄色为市色,该提案经议决通过,这说明直到民国中期,20世纪初年所形成的以黄色作为民族国家象征色彩的含义,仍然在得到了继承和重视,甚至可以说,它继续构成许多中国人现代民族国家意识及认同的有机组成部分。 然而,具有讽刺意味的是,十年之后,中国人长期珍重、近代以降又格外赋予其民族象征意义并声称应保护其纯洁的黄色,在社会流通层面竟然迅速地加入了庸俗和淫秽之义,而且这一负面含义日益显豁和占优,与象征高贵、尊崇的传统涵义矛盾并存。在这一变化过程中,正如许多学者所已经指出的,西方有关黄色概念的传入,无疑产生了直接影响。 1924年,《国闻周报》认为国外黄色新闻就是那些刻意耸人听闻、引人兴趣的新闻,而所谓动人耳目之新闻者,不外乎各地暗杀、抢劫、离婚、苟合之事。在随后30年代中期至40年代初期,国内对黄色新闻概念的介绍和使用逐渐增多,到40年代中后期,黄色新闻语义的变异忽然加速,色情的主导含义得以迅速确立。 黄色一词含义的巨大转变在一方面是受到西方文化的影响,而另一方面更加显示了国人 《解读大众文化》第二章“消费的快乐”阅读笔记 ——理想大众观念下的消费观简论作为较早将约翰·菲斯克文化研究思想介绍到国内的学者,陶东风有一段这样较为精辟的概括:“日常生活的审美化以及审美活动日常生活化深刻地导致了文学艺术以及整个文化领域的生产、传播、消费方式的变化,乃至改变了有关’文学’、’艺术’的定义”,因此, 文艺学应该正视审美泛化的事实,紧密关注日常生活中新出现的文化\艺术活动方式,及时 地调整、拓宽自己的研究对象和研究方法”。的确,在一个被Lady Gaga(被称为后麦当娜)、 新媒体(微博,微信)、广告时装充斥的社会,传统的学院派文化研究方法已经不能很好的胜任分析工作,在约翰·菲斯克的《解读大众文化》一书中,研究和批评的界限被无限放大和细化,作者用显微镜一般的视角观察、审视走向日常生活的文化,并将文化分析、社会历史分析、政治经济分析综合运用,不仅仅简单揭示对象的审美特征,还解读了其中含有的文化生产、消费以及政治经济之间的复杂关联。 在《解读大众文化》一书中,购物广场、海滩、电子游戏、麦当娜…这些常见的事物都 成了菲斯克笔下的大众文化符号,菲斯克认为,大众在日益复杂化的符号战场上组织、规避、对抗社会霸权,从而获得快感和意义。在菲斯克的理论构建中,大众不像法兰克福学派主张的那样受到压制乃至无力反抗,相反,他的理想大众是能动的、创造的和抵抗着的,这是理解《解读大众文化》的第一步。同时,菲斯克在第一章对大众文化也做了较为明确的界定,他认为大众文化是大众利用现有文化资源进行创造性活动的活生生的实践过程,他将大众文 化视为“有啥用啥的”(the art of making do)(P18,由于原文翻译的不是很好,这句是 我自己翻译的)的艺术,大众文化是在大众与社会较为强势的一方主动或者消极“对抗”时产生的一种潜意识文化。 带着这样的前提,前往第二章的阅读,菲斯克将意识形态和霸权话语理论带入到购物广场中,赋予日常生活形态陌生感,让读者重新审视、思考这一再普通不过的行为。根据布尔迪厄的“场域理论”,场域是一个竞技场,一个踏进其中的人或有意识或无意识之中,都在被场域中的位置、设置、策略影响着,与对立方展开斗争。菲斯克将购物广场类比为一种神圣的战争场域,于是简单的购物充满了阶级意识的火药味:相对弱者(大众)在“游击战场 一般的购物广场”中颠覆、对抗着强者(资本持有者),因为菲斯克认为“文化(及其意义和快乐)是社会实践的一种持续演进,因而它具有内在的政治性,它主要涉及各种形式的社 会权力的分配及可能的再分配”,在这样的理论前提下,这种购物战争似乎也算不上是过度阐释。在一个给定场域内分析既定行为之间的权利分配关系,是许多后现代理论家诸如大卫哈维和布尔迪厄关注的焦点之一,这也是自列斐伏尔、福柯以来的空间转向传统。可以说在第二章菲斯克的论述中,可以看到空间批评的影子。青少年娱乐亚文化及其发生

浅谈电视剧艺术的大众文化属性

网络语言文化透析及其语言规范标准

组织变革与组织文化

中国传统文化近代以来发生了哪些变化.

文化大繁荣背景下的国学热现象的透析

网络用语文化现象分析

论网络青年亚文化的研究现状及反思

李白研究领域的新开拓——何念龙研究员新著《李白文化现象论》读后

中国传统文化的过去和传承以及发展

从原始文化现象透析礼仪的本质_来玉英

中国文化现象

新媒体环境下青少年亚文化的_新风格化_

[传统文化,中国,含义]浅析“黄色”一词含义历史变迁及中国传统文化反思

解读大众文化.别人的阅读笔记